Keeping Coeur d’Alene Lake’s Water Quality in Check

Did you know Coeur d’Alene Lake is part of the Bunker Hill Mining and Metallurgical Complex Superfund Site? A recent Our Gem community survey revealed fewer than 30 percent of respondents were aware the Lake is included in the Superfund Site. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) listed the site on the National Priorities List in 1983, which seeks to address legacy impacts of mining, primarily heavy metals contamination. The Superfund Site consists of three distinct areas, one of which includes mining-contaminated areas of the Coeur d’Alene River, adjacent floodplains and Coeur d’Alene Lake itself.

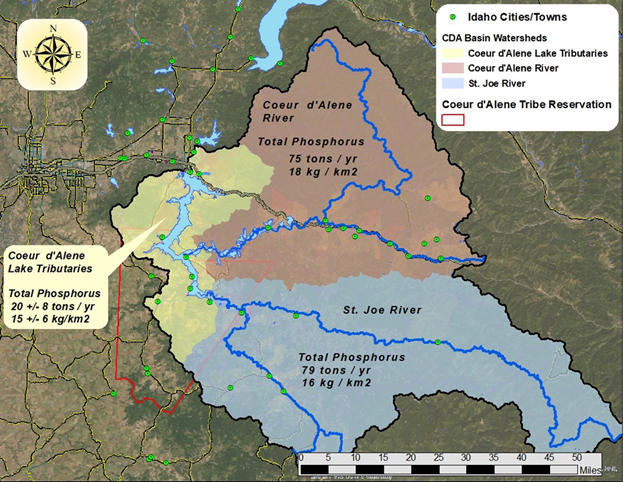

In 2009 the Coeur d’Alene Tribe (Tribe) and Idaho Department of Environmental Quality (IDEQ), with input from other local, state and federal agencies, finalized a Lake Management Plan (LMP), a collaborative effort aiming to protect and improve Lake water quality by addressing pollutant loading on a watershed scale.

While Coeur d’Alene Lake has heavy metals contamination (of lead, cadmium, zinc, antimony, etc.), in cold, clear and nutrient-poor waters most of these metals stay locked away in lakebed sediments. Fortunately, the waters of Coeur d’Alene Lake have historically been just that: cold, clear and nutrient-poor! Unfortunately, water quality monitoring has shown nutrient level increases in the lake since 2015, which could have serious consequences for the millions of tons of metals-contaminated lakebed sediments.

When nutrients, particularly phosphorous, are washed into Coeur d’Alene Lake, aquatic plants and algae respond with big boosts in productivity, rapidly reproducing due to this hearty dose of fertilizer. When these plants and algae die, they sink to the Lake bottom where they are broken down by decomposers like bacteria. These decomposers consume dissolved oxygen and release dissolved carbon dioxide, which results in the water becoming more acidic than it would otherwise be. As water at the bottom of the Lake becomes more acidic, the heavy metals are released from the lakebed sediments and dissolved into the water column, where they enter the food web. Many of these metals, particularly lead, bioaccumulate in the plants and animals that call the Coeur d’Alene watershed home.

While the LMP partnership between the Tribe and IDEQ has generated a tremendous amount of encouraging data on the lake’s water quality, it has also shown that some measures of water quality, like nutrient loading, are trending in the wrong direction. The LMP includes water quality thresholds that, if approached or exceeded, trigger a comprehensive review of the data in hopes of rapidly identifying pollution sources and appropriate management actions. In 2019 the Tribe notified IDEQ and the EPA that they could no longer support the LMP and officially withdrew from the LMP partnership citing the declining lake’s water quality as evidence of the LMP’s ineffectiveness. Though no longer LMP partners, both the Tribe and IDEQ continue to aggressively study lake dynamics with the support of the EPA.

The future of Coeur d’Alene Lake is less certain than it’s ever been, but there is no shortage of good work being done by the Tribe, IDEQ, the EPA and others. Later this year a comprehensive report from the National Academy of Sciences on lake water quality is expected. Also, in response to increasing nutrient loading, Idaho Gov. Little allocated $2 million to fund nutrient reduction projects, with 11 projects scheduled to begin work in 2022. Coeur d’Alene Lake undoubtedly faces challenges, but Tribal, State and Federal agency staff, working with the local communities, are committed to its future health and the quality of life it provides the communities that rely on it.