Vandals Deliver A Life-Saving Gift

Vandals Deliver A Life-Saving Gift

University of Idaho College of Engineering students help WWAMI Medical Education Program student overcome spinal cord injury in quest to become CPR-certified.

Engineering, WWAMI Medical Students Build Assistive CPR Device to Help More Users, and Those With Disabilities, Successfully Perform CPR

For Meagan Boll, being a successful physician is about building trust.

“There’s no way to effectively treat a patient if they don’t trust you,” Boll said. “One way to build that up is through one-on-one interactions.”

A second-year medical student in the Idaho WWAMI Medical Education Program, Boll uses a wheelchair, has limited motion in her arms and performs fine motor skills with a bionic glove. A spinal cord injury that caused impairment in all four quadrants of her body is also what got her interested in pursuing medicine.

To assess patients, Boll, from Cambridge, Idaho, uses a Bluetooth stethoscope with headphones and an ultrasound wand for abdomen inspections. But she cannot perform traditional CPR and therefore a certified CPR assistant is required to be in exam rooms with her and her patients.

“Getting CPR-certified provides me the opportunity to have one-on-one consults, which would help build patients’ confidence in my ability to deliver care,” she said.

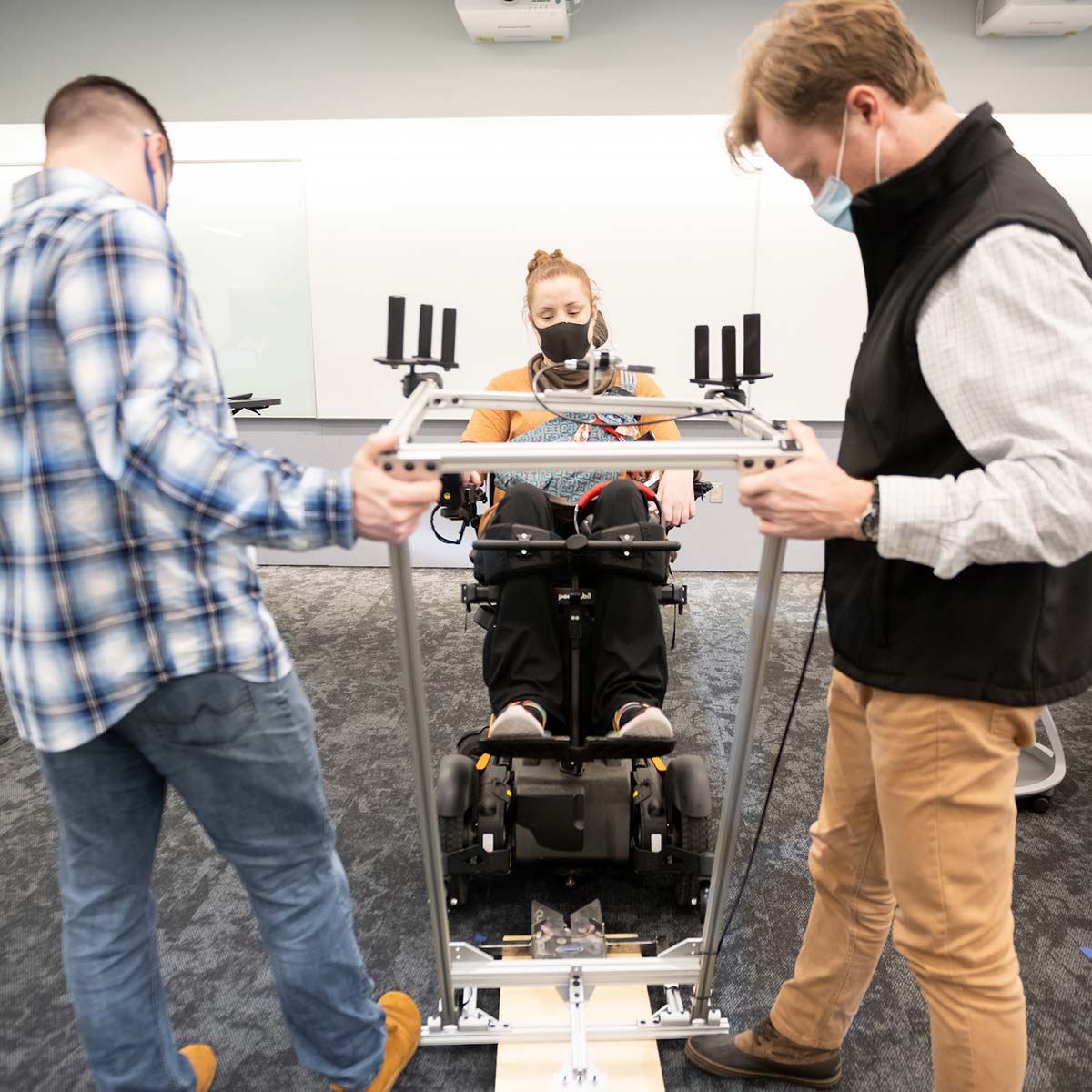

To help Boll, University of Idaho College of Engineering students developed an assistive CPR device custom for her, with application across a spectrum of users with limited arm strength or other disabilities.

Breaking Down Barriers in Healthcare

According to the Reeve Foundation, nearly one in 50 people are living with paralysis. Choosing a career in healthcare may be daunting for people with paralysis because of physical requirements.

“Many people aren’t aware, but CPR is incredibly physically demanding,” said Jeff Seegmiller, director of WWAMI at the University of Idaho and professor in the Department of Movement Science at U of I. “Effective CPR can sometimes lead to a cracked or broken rib.”

A broken rib may be worth it, considering 475,000 people in the United States die from cardiac arrest each year, according to the American Heart Association. Nearly three-fourths of these cases occur outside a hospital and having a CPR-certified bystander nearby improves victim survival rate by nearly 45%.

“Any opportunity we have at the University of Idaho to innovate and break down barriers due to disabilities allows more very capable individuals, who have the intelligence and heart, to become healthcare providers,” Seegmiller said.

Boll worked with U of I mechanical engineering students Abdulrahman Almajnouni, Ahmed Al Nahab and Josh Sewell as well as materials science and engineering student Tyler Newman to design an assistive CPR device.

Seegmiller proposed the project as part of the College of Engineering’s nationally recognized Senior Capstone Design Program, during which students work on industry-sponsored projects to design thoughtfully engineered, tested and validated prototypes.

“In the process of understanding this project more and understanding quadriplegia, the word independence comes up a lot,” Sewell said. “Designing a device like this can help Meagan achieve that in her profession and can also help others with disabilities or limited strength save lives.”

“In the process of understanding this project more and understanding quadriplegia, the word independence comes up a lot. Designing a device like this can help Meagan achieve that in her profession and can also help others with disabilities or limited strength save lives.” Josh Sewell '20, U of I Mechanical Engineering Graduate

Leave It to the Lever

To successfully perform CPR, the American Heart Association recommends exerting enough force on the base of the sternum to compress the chest 1.5 to 2 inches – which can mean exerting up to 100 to 120 pounds of force on an adult victim. This force must also be sustained at a rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute.

To achieve proper compression in their design, the engineering student team tested the idea of using a method similar to a fingernail clipper and discussed several mechanical options.

“We knew we needed to multiply the applied force out to achieve compression,” said Newman. “The easiest way to do that is through a lever.”

The assistive CPR device is a modern version of a simple and primitive concept, one that goes back as far as Greek mathematician and engineer Archimedes’ “law of the lever,” proving force is amplified when transferred via a lever and a fulcrum.

The team’s first prototype clipped to the side of Boll’s wheelchair, requiring her to drive her wheelchair beside the victim and operate the wooden lever with one hand.

Since Boll’s finger mobility is limited, she suggested adding another handle to the design. The device was also upgraded to attach to the front of Boll’s wheelchair using a modified securement system like the one Boll uses when driving a car so that she can push forward to operate a lever placed on the victim’s chest.

The lever-action augments Boll’s force to achieve necessary chest compression. Using a training mannequin connected to a mobile app to record CPR performance, the team verified their results and Boll’s successful use of the custom device.

Abdulrahman and Al Nahab did much of the computer-aided design work and machining of the device. Building their final design in lightweight aluminum allows for easier use and mobility.

The College of Engineering is looking into ways a simpler version of Boll’s custom device could be manufactured for use in nursing homes and hospitals to help those who may not have the arm strength or stamina needed to complete CPR.

Clerkships are Coming

After Boll completes her medical exams this year, she will prepare for 42 weeks of required clinical clerkships in family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry and surgery. The assistive CPR device provides her with options for clerkships that may not have been available to her otherwise.

“Idaho WWAMI faculty have been so supportive of me and my goal of becoming a doctor,” Boll said. “This device helps open up even more possibilities in my career.”

Written by Lindsay Lodis, WWAMI and Alexiss Turner, College of Engineering

Photos by Joe Pallen

Video by Kara Billington and Will Knecht